On Helicopter Money

As current emergency times call for serious action from monetary and fiscal authorities alike, a famous topic to pop up in these discussions is "cash handouts" for the people financed by central bank money creation, or more familiarly, helicopter money. Here, I will try to elaborate on why helicopter money may turn out to be a policy that will backfire into a constant need of covering ECB losses, or more gloomily, a refinancing "death-loop" that could wreak havoc throughout the whole monetary system as it is currently functioning. As a case example, and maybe here as the "most likely" one that will have to rely on some sort of helicopter drops, I will be using the European Central Bank (ECB).

In a fiat monetary policy framework, short-term interest rates are either controlled mainly through reserve scarcity (a corridor system) or when reserves are abundant, through deposit rates (a floor system). Currently, the monetary policy implementation method used by the ECB is a "floor system" like it is in the US. As a "floor" for short term interest rates, we have the deposit facility rate, which is currently set at -0.5%. This is the rate what the ECB pays on deposits or reserves held at the ECB. In a "floor system", short term interest rates are controlled by increasing and decreasing the deposit facility rate. As reserve balances are abundant, manipulation of the number of reserve balances has no effect on the margin, like it had before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). To have a more detailed explanation of how monetary policy is implemented after the GFC, please refer to my previous blog post (even if my previous post is told from the perspective of the Fed, ECBs monetary policy implementation largely follows the same logic, replacing the discount window with the marginal lending facility and assuming its actual usage).

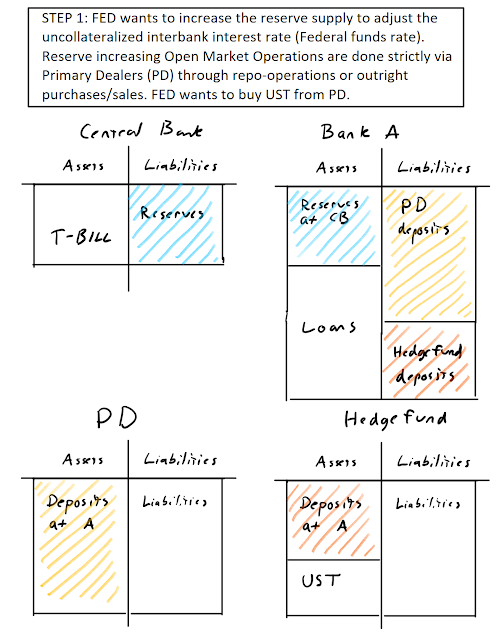

In a conventional Quantitative Easing program the ECB buys mostly government securities through its Primary Dealers (PD) in order to suppress long term yields by reducing their supply in the market. When the supply of a good (in this case Government Bond) decreases, all other things being equal, its price increases. As for bonds, the relationship between the price and yield is inverse, it means that the yield on these bonds goes down, suppressing the interest rate governments need to pay if they are to refinance their debt. This purchase of government assets through PD increases the reserve balances at the PD's bank while increasing deposits of PD. This manifests in a net increase in the size of the ECB's balance sheet. On the asset side of the ECB's balance sheet, we have interest-paying Government Bonds and on the liabilities side, we have reserves (which currently also pay a negative interest rate to the ECB). For the PD this is an asset swap, where a government bond is transformed into deposits and for the bank where PD has its deposit account reserve balances increase (and so does the amount PD's bank has to pay "bank tax" to the ECB). New money is thus issued into existence.

Every year, the income ECB gets from the assets it holds is paid to the eurozone countries according to their "capital keys" which is a function of population size and GDP. This means, that the bigger the size of the balance sheet of ECB and the more negative the interest rates are on reserve balances, the greater the amount of money that is paid to governments each year. If however, the rates that are paid on deposits held at the ECB are positive, the ECB has to pay to banks and thus covers these money outflows through interest paid on its asset holdings or, if it cannot, the eurozone governments should step in and pay them. Alternatively, ECB could go bankrupt, being unable to meet its liabilities.

Below is a simplified example of the current framework. ECB holds eurozone government bonds and gets interest paid on them and, additionally, has negative interest paid on reserves that banks are forced to hold at ECB. If the ECB's investments are making a profit, the eurozone governments are the ones getting paid. As most of ECB investments are in government bonds, the same governments "benefitting" here are the same governments that are liable to pay interest on the assets ECB holds. As in eurozone, the bonds ECB holds are not distributed equally according to how it pays out interest income at year-end, it means that in a currency union, some countries are obviously profiting and some relatively losing. If ECB was only to hold bunds (German government debt securities), it still has to distribute its income according to capital keys. Here, Germany would be financing other eurozone governments through ECB. In a country that has its own currency, the profits are directly distributed back to the "owning" government. An example of this would be the United States. Nevertheless, in this framework, the ECB can continue to function without bankruptcy, assuming that the bonds it holds are NOT constantly "mark to market" valued, especially during a crisis. If ECB sees a need (inflation) to increase short term interest rates from -0.5% to 1%, it will have to hike deposit facility rates as it is the de facto rate that controls the short-end of the curve in the eurozone. This operation will make its own portfolio less profitable as this would manifest in a POSITIVE interest rate paid on its reserve balances thus gradually eating out the interest ECB gets paid on its assets as short-term rates need to be increased. If we are to assume mark-to-market, this could also show in long term yields and thus on the market value of assets held at the ECB (and potentially eat out ECB's capital and push it into bankruptcy).

In a fiat monetary policy framework, short-term interest rates are either controlled mainly through reserve scarcity (a corridor system) or when reserves are abundant, through deposit rates (a floor system). Currently, the monetary policy implementation method used by the ECB is a "floor system" like it is in the US. As a "floor" for short term interest rates, we have the deposit facility rate, which is currently set at -0.5%. This is the rate what the ECB pays on deposits or reserves held at the ECB. In a "floor system", short term interest rates are controlled by increasing and decreasing the deposit facility rate. As reserve balances are abundant, manipulation of the number of reserve balances has no effect on the margin, like it had before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). To have a more detailed explanation of how monetary policy is implemented after the GFC, please refer to my previous blog post (even if my previous post is told from the perspective of the Fed, ECBs monetary policy implementation largely follows the same logic, replacing the discount window with the marginal lending facility and assuming its actual usage).

In a conventional Quantitative Easing program the ECB buys mostly government securities through its Primary Dealers (PD) in order to suppress long term yields by reducing their supply in the market. When the supply of a good (in this case Government Bond) decreases, all other things being equal, its price increases. As for bonds, the relationship between the price and yield is inverse, it means that the yield on these bonds goes down, suppressing the interest rate governments need to pay if they are to refinance their debt. This purchase of government assets through PD increases the reserve balances at the PD's bank while increasing deposits of PD. This manifests in a net increase in the size of the ECB's balance sheet. On the asset side of the ECB's balance sheet, we have interest-paying Government Bonds and on the liabilities side, we have reserves (which currently also pay a negative interest rate to the ECB). For the PD this is an asset swap, where a government bond is transformed into deposits and for the bank where PD has its deposit account reserve balances increase (and so does the amount PD's bank has to pay "bank tax" to the ECB). New money is thus issued into existence.

Every year, the income ECB gets from the assets it holds is paid to the eurozone countries according to their "capital keys" which is a function of population size and GDP. This means, that the bigger the size of the balance sheet of ECB and the more negative the interest rates are on reserve balances, the greater the amount of money that is paid to governments each year. If however, the rates that are paid on deposits held at the ECB are positive, the ECB has to pay to banks and thus covers these money outflows through interest paid on its asset holdings or, if it cannot, the eurozone governments should step in and pay them. Alternatively, ECB could go bankrupt, being unable to meet its liabilities.

Below is a simplified example of the current framework. ECB holds eurozone government bonds and gets interest paid on them and, additionally, has negative interest paid on reserves that banks are forced to hold at ECB. If the ECB's investments are making a profit, the eurozone governments are the ones getting paid. As most of ECB investments are in government bonds, the same governments "benefitting" here are the same governments that are liable to pay interest on the assets ECB holds. As in eurozone, the bonds ECB holds are not distributed equally according to how it pays out interest income at year-end, it means that in a currency union, some countries are obviously profiting and some relatively losing. If ECB was only to hold bunds (German government debt securities), it still has to distribute its income according to capital keys. Here, Germany would be financing other eurozone governments through ECB. In a country that has its own currency, the profits are directly distributed back to the "owning" government. An example of this would be the United States. Nevertheless, in this framework, the ECB can continue to function without bankruptcy, assuming that the bonds it holds are NOT constantly "mark to market" valued, especially during a crisis. If ECB sees a need (inflation) to increase short term interest rates from -0.5% to 1%, it will have to hike deposit facility rates as it is the de facto rate that controls the short-end of the curve in the eurozone. This operation will make its own portfolio less profitable as this would manifest in a POSITIVE interest rate paid on its reserve balances thus gradually eating out the interest ECB gets paid on its assets as short-term rates need to be increased. If we are to assume mark-to-market, this could also show in long term yields and thus on the market value of assets held at the ECB (and potentially eat out ECB's capital and push it into bankruptcy).

Now there are few ways people propose helicopter drops to be implemented. I am going to explain the caveats through direct cash handouts to citizens deposit accounts at a commercial bank as this is the "most radical" proposal, usually coming from those not familiar with technical mechanisms of central banking. Having money deposited to "citizens central bank accounts", where there is a possibility to deposit money into them, is not a realistic option as it would be forcing bank runs and causing a serious threat of financial crisis, possibly collapsing the whole private banking sector. This is because all the money that is transferred from an ordinary deposit account at a commercial bank to an ECB account causes drainage in the number of reserves in the banking system, possibly forcing banks into a liquidity crisis.

For cash handouts implemented through commercial bank deposit accounts, the situation is better, but not without technical problems. The idea of how a "helicopter drop" works is through a permanent increase in the central bank balance sheet (or base money) as a zero interest-bearing asset with infinite maturity. The ECB lends to each citizen (perpetual bond), depositing their account with money. This increase in deposits increases the reserve balances of the banking system and so the liabilities the ECB has to pay interest on (if the rate paid on deposits is above 0). The more money that has been created this way, backed by zero-bearing assets, the less profitable ECB's balance sheet becomes and in the example below, it can even become a loss generating portfolio. Thus if there ever is a need to increase short-term rates above 0, the ECB must, under the current monetary policy implementation regime, achieve it through increases in deposit facility rates and so aggravating the problem of losing portfolio. This loss will have to be covered by eurozone countries if we are to avoid ECB bankruptcy (another option would be to speculate on equity markets and try to "beat the market" forever and ever in order to achieve profits that would cover ECB losses). In a positive short-term interest rate environment, this increases the fiscal burden of governments and causes a "death-loop", because of the constant need of covering ECB losses as long as cash handouts are given and not unwound. The bigger the absolute size of the balance sheet is, and the higher the short term rates are set in order to e.g. fight inflation, the higher the need is for eurozone governments to pay the bill. In essence, in a complete helicopter money world, there is NO case for hiking short-term interest rates, without causing failure for the ECB (and in the end, eurozone governments) to meet their interest obligations. In a "traditional" QE, this issue is also somewhat prevalent as bought debt securities are having a lower and lower coupon, but it still comes with a "normalization" expectations, i.e. it is not supposed to be a permanent increase. Unwinding central bank cash handouts can realistically be thought to be politically impossible.

Interestingly, during times of negative interest rates on government debt securities and when the deposit facility rate is higher than the government's debt financing rate, every "helicopter drop" if given directly to governments manifests into less favorable financing terms. ECB fiances your perpetual bond at, say 0%, while from capital markets you can have a rate of -0,5%, which essentially does not have to increase reserve balances at all.

The bottom line here is, that even if we are not to dwell on issues of loss of central bank indepency and thus endless political demands for ending all problems in the world through cash handouts, the issue is rather technical to begin with. If we are to have helicopter drops, we should have new ingenious ways to implement monetary policy in the first place. If this is not a topic that is even discussed as it is now, the helicopter handouts might end up collapsing the whole system solely on technical grounds.

Comments

Post a Comment