Why Central Bank balance sheet expansion during COVID19 is not pumping asset prices

As there still seems to be major confusions regarding central bank actions and what it means for the financial markets in general, I decided to try "one last time" to explain in maybe one of my most detailed posts on how different balance sheets across sectors of financial markets react to central bank policy and how financial markets are supposed to work in "normal times". The essential message of this post is the same as that of my previous short post on covid crisis, but this time with more rigorous technical exposition.

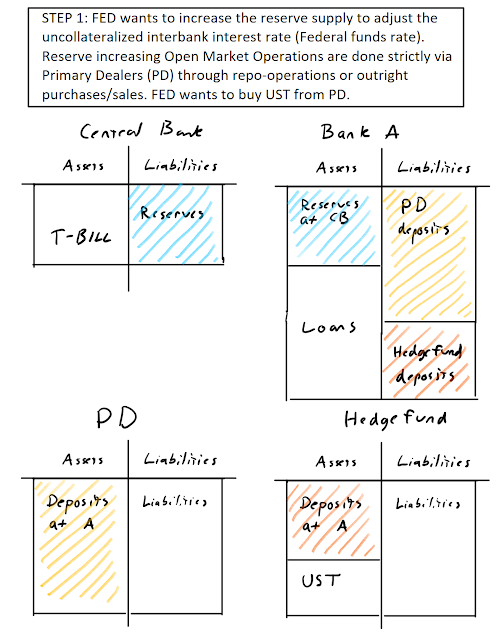

As I have explained here in detail, the monetary policy implementation method since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) is a so-called "floor system", where in theory, the interest rate on excess reserves (IOER) works as a lower bound for short term interest rates in the economy. In short, this is because the reserve supply greatly exceeds that of which there is demand for in the banking system as a whole, thus, in theory, the competition among financial institutions pushes the short term interest rate to be glued to the IOER. However, as not every institution having an account at the Fed is eligible to earn interest on reserves, there is an incentive for these institutions to lend all reserves out at a rate higher than 0, providing a positive carry to depositary institutions enjoying IOER on their reserves (borrowing below IOER and depositing at the Fed to earn IOER and reaping the spread as a profit). Thus, the actual lower bound is practically achieved through Feds Reverse Repo operations (RRP), where the Fed withdraws liquidity from the market by borrowing reserves against collateral held at its SOMA account. The RRP rate is currently set at 0%. As of 15th of March the reserve requirement was set to 0%, first time ever, depository institutions can now earn IOER on the total amount of reserves they are holding at the Fed. For the Fed the monetary policy objectives are to ensure financial stability, price stability with 2% inflation target and full employment. In order to achieve this, Fed control short term interest rates setting a Federal Funds Target rate Range with IOER top of the band and RRP the bottom. All though, Fed mainly targets the effective federal funds rate (EFFR), its objective includes implicitly controlling all short term rates. I have written about how this objective manifests in also having an effect on long term rates here (unfortunately only in Finnish).

Now as I hopefully have convinced the reader (especially if you had the time to read my previous post on floor system) that IOER, in fact, functions as a lower bound for short term interest rates (ignoring RRP for simplicity), I can turn to explain how financial markets functioned still last year during the so-called "normal times".

The financial sector depicted below has the Fed, Hedge Fund (HF), Bank A, Bank B, Bank C, Broker, and a Money Market Fund shown. The balance sheets of these institutions are highly simplified in order to keep the flow of funds more easily traceable. No interest payments are shown, as it would complicate matters. We are here assuming reserves paying 1% interest on the full amount held at the Fed (IOER = 1%).

The state of our financial economy starts as below. The HF is just starting its business and eyeing an opportunity to buy 100$ worth of Apple's Commercial Paper.

In order to achieve this, HF needs to borrow as its starting equity is just a mere 20$. The HF goes to its Bank A and gets a loan of 80$. The assets and liabilities of bank A increase, i.e. the balance sheet of Bank A expands, the same happens for HF. New deposits are created.

Next, HF purchases 100$ worth of Apple Commercial Paper from the Broker. In order to make the transfer, Bank A has to borrow funds on the Federal Funds markets, from Bank C in this case, paying an EFFR rate of 1% for its borrowing.

As HF was paying a high rate on its initial borrowing, HF decides to roll over its borrowing as a repo using the Apple Commercial Paper obtained as collateral. Apple Commercial Paper is deemed riskier than the 10y US Treasury repoed by Bank C, thus it is repoed with a 20% haircut, enabling HF to obtain only 80$ of funding against 100$ worth of Apple Commercial Paper. Note, that 10y UST can be repoed without a haircut, thus Bank C can fund its US treasury portfolio fully with cheap repo financing. The broker decides to pay off its repo borrowing with the deposits obtained from selling the Apple Commercial Paper.

In order to pay the Federal Funds loan from Bank C, Bank A borrows funds from Bank B.

All these transactions are made possible by normally functioning markets, e.g. the market that still existed before the COVID crisis really hit western economies in March 2020. Some could argue, that the markets last functioned normally before the "repocalypse" of September 2019 or on even more cynical note, before the GFC, when we still had a "corridor" operating system. Anyhow, as long as financial market parties are willing to borrow and lend "freely", there is no need for the Fed to expand its balance sheet. All transactions are made possible by the use of private balance sheets only. As we can see above, the financial markets balance sheets expands and contract as transactions are made. The private balance sheet capacity is ample and from the perspective of a security speculator such as the Hedge fund, all that matters is what is the respective financing rate for their portfolio. The interest rate that is indeed bound below by Fed setting IOER. When money markets function normally, the rate at which different parties can borrow funds is generally really low, especially on repo markets.

Now, imagine, that the latest transaction (borrowing from B to pay C) was not made and instead, the Fed sees some pressure in US treasury markets, causing illiquidity (widening bid-ask spreads) in US treasury securities and causing unwanted volatility in the price of USTs, threatening financial market stability. The Fed decides to intervene through the use of Quantitative Easing (QE) programmes, that is, by purchasing long term treasury securities from the secondary markets. It can be argued that interventions like this (also which happened during the first covid crash) are not QE-programmes in the traditional sense, as the intention, is not to lower yields at the long end of the curve by increasing on net demand for Treasury securities (and reducing their supply) and thus lower its yield but to ensure market liquidity and ample reserves in the stressed financial system. From the perspective of the bank (ignoring non-bank primary dealers, which would manifest also into an increase in bank deposits) this is merely an asset swap where US treasury security is exchanged to an equivalent amount of central bank reserves. This is where the balance sheet of the Fed first expands in our example. When the Fed sees a deficiency in private asset demand, it will intervene by becoming a "dealer of last resort", supplementing the suddenly lost demand by expanding its balance sheet. On net, no new demand is created compared to a baseline of normally functioning markets.

The increase in reserves for Bank B enables it to pay off its federal funds loan from bank C. Note, that all though this did increase the aggregate reserves in the banking system, it does not manifest in lowering short term interest rates, which is used to finance speculative and dealer positions as the short term rate is in an ample reserve supply regime bound below by interest rate paid on excess reserves. Obviously, if the Fed had not intervened this rate would have shot up, making the financing conditions for speculative players more troublesome, but remember, by its mandate, the Fed will always control all short term rates. Thus, comparing to a baseline of "everything functions as normal" is essential here. Compared to that case, the increase in reserves does not cause any excess demand for anything, it only supplements lost demand. We can so induce, that the "brrr'ing" of money printer should not manifest into "pumping stock prices" as many seem to claim.

The essential real factors for "stock pumping" are

a) if intervention increases demand relative to baseline

b) if an increase in reserves pushes short term financing rates lower (that is, reserves were not ample to begin with, which is not the case here)

Next, the Broker will wish to increase its holding of Apple stock by 80$. As the broker is lacking the necessary funds, she has to fund her position by borrowing money from Bank B.

The Broker purchases 80$ of Apple stock from Bank C. As stocks are not usually used as collateral for repo, the Broker has to keep funding its position in Apple stock by borrowing at a considerably high rate from Bank B (essentially having its own balance sheet as a collateral). The following transactions occur.

As stresses continue to spread, all creditor institutions become hesitant to lend money at a reasonable rate. Bank A refuses to roll over HFs short term loan and so does every other institution capable of lending. The same happens to the broker who is unable to roll over its loan from Bank B. The hedge fund and broker may now both be forced to liquidate their positions to already illiquid market taking serious losses, possibly causing their insolvency. Now, remember that Apple as a company is also in trouble if money market freezes as it also becomes unable to roll over its short term debt at a "reasonable rate", threatening insolvency also for Apple. This is extremely worrying in a crisis like the one we are having now, where businesses are ordered to be shut down and people are locked into their homes. Even if companies are ordered to close, they still have running liabilities to meet and due to drying cash inflows the need for short term credit might even increase (paying salaries etc.). Luckily for the market, the Fed and US government sees and understands the pressures building and decides to act. The Fed with the help of the US treasury will be now providing liquidity to the commercial paper market and so the Fed is indirectly becoming a "dealer of last resort" for this market as a whole. A special purpose vehicle (SPV) is set up where the US treasury first injects 10$ of loss-absorbing capital and then the SPV borrows 90$ from the Fed and after that, the SPV uses these funds to purchases 100$ of commercial paper from Money Market Fund. This SPV is in the real world called a Commercial Paper Funding Facility or CPFF. The Fed balance sheet expands and new reserves are created.

This Fed intervention calms the market as Fed steps up to supplement the lost demand on money markets. Repo markets reverse back to a pre-shock state and HF is able to pay off its expensive borrowing from Bank A and to use Apple Commercial Paper as collateral for cheap repo funding. Also, the broker is once more able to get cheaper funding from Bank B.

Lastly, let's assume another repo hiccup, this time on the most liquid repo market, e.g. general collateral repo. Imagine that for some reason nobody wants to roll over Bank C's GC repo at a reasonable rate (happened in September 2019 where GC repo went above 10%). The Fed now steps in and becomes the lender of last resort, becoming a repo counterparty to Bank C instead of MMF. This once more increases the amount of reserves in the banking system as a whole, but from the perspective of financial institutions, the amount of reserves itself is rather irrelevant. The most important question for financial institutions is, "What is the rate at which I can fund my positions?". If the increase in reserves does not manifest in lower rates, then the effect is only through increase in demand, but compared to a baseline it might be just supplementing the lost demand as best as possible. Thus, there may not be any reason to expect increasing asset prices due to policy intervention.

So what have I demonstrated here? Firstly, I hope that I have convinced the reader that in a crisis situation such as the one we are in now, the money printer might only be helping to supplement lost demand, and thus there is no real direct link on increase in reserves itself manifesting to increasing asset valuations. But real links are not all that there is, there still might be an effect on expectations. E.g. expectations that the Fed will also in the future be ready to step up and prop up falling markets or expectations of Fed getting irresponsible and causing on net, excess demand to markets at large, boosting inflation and asset valuations in midst of a biggest economic lockdown of our lifetime. If that net increase in demand compared to a "normal" baseline would actually happen now, there certainly would be reasons to expect that these actions would be pumping asset valuations, but this has nothing to do with the amount of central bank reserves there are in the system banking system at large. Putting it simply, the Fed is just another creditor in the US financial system and by its mandate, the Fed has to intervene in order to preserve financial market and price stability.

To those betting their money on prospects of the Fed currently pumping stock prices, I have got bad news for you. As of now, there is really no real reason for it as no new demand is created and private balance sheet capacity is vanishing at an astonishing pace. There is no reason for excess risk-taking in this environment either. Especially after seeing the recent Oil futures market crash causing the most drastic tail event in oil market history, I am doubting that any risk manager is currently at ease and willing to allow an increase in risk-taking during the unprecedentedly uncertain times we are living. At least to me, it would make absolutely no sense. There is also no argument for a "search for yield" during times like these, rather the opposite. The demand for safe assets is off the roof and financial institutions, mandated by law to hold a certain amount of sovereign debt in their balance sheets have absolutely no reason to stop doing that, if anything, there is plenty of reason to increase those holdings. This is especially the case for US treasury securities, which is almost in the status of being a lifeline for the global monetary system, especially in a crisis. Secondly, company earnings are plummeting. If there exist no real monetary reasons for an increase in asset prices as exposed above, then the earnings yield should also only plummet from here, making the case for "search for yield" even less rational. Essentially, there is no yield to search for, when demand disappear and earnings become losses. To me, the current stock market route signals greed and denial at the level last seen during 2017 cryptocurrency crash. The false hopes generated will turn out to be painful for many as we will once again find that the emperor has no clothes.

Comments

Post a Comment